Springfield has many opportunities for small-scale development

BY CATHERINE O’CONNORGoverning magazine recently published the results of an in-depth investigation into segregation in Illinois communities, including Springfield. A recent cover story in Illinois Times included excerpts from the lengthy report (“Segregated in the Heartland, Feb. 7), which also focused on income disparity between black and white Springfield households. Pouring through U.S. Census data, state and federal school enrollment data, government documents, interviews with elected officials and academic reports, the magazine found that ”…no Illinois city displayed its segregation more plainly than Springfield, marking the city’s dividing line at the railroad tracks along 10th Street.” Finding that median black household income was a mere 42 percent of that of whites in Illinois’ capital city, the report pointed out that “west of the tracks, the neighborhoods got progressively whiter and wealthier.” Polly Poskin, the vice-chair of Inner City Older Neighborhoods (ICON), is one crusader who is bothered by the economic indicators showing black residents here are far more likely to be surrounded by poverty than whites, at rates higher than all of the downstate Illinois cities studied by Governing. Understanding that nowhere does the ‘power of place’ exert itself as visibly as in the neighborhoods that many of Springfield-area minority residents call home, she would like to see the city, developers and “profiteers” work together to find solutions. Poskin asserts the need to ask how zoning, land-use patterns and limited location opportunities for moderate-income, residential rental units have created a landscape that seems to keep black families segregated from whites. Mayor Jim Langfelder, who was interviewed by Governing said, “It’s driven by private development and what’s available in the city.” Poskin suggests that a natural place to start would be by asking large, successful developers whose projects have led the westward expansion, how smaller scale developers can start to make a difference.

JOHN KLEMM John Klemm is a longtime west-side developer and Realtor who has seen decades of change in the capital city. He has been involved in large-scale residential developments west of Veterans Parkway such as Cider Mill, Panther Creek and Savannah Pointe. According to Klemm, the city could benefit from master planning that would include updating infrastructure, like water and sewer lines in older neighborhoods, as well as streamlining administrative requirements that often make development agreements difficult to maneuver. Jessica Weitzel, who is a lending officer at LISC, a nonprofit corporation based out of Peoria, has noted that in some cities, developers of open space that is annexed for new developments like Klemm’s are asked to contribute impact fees. This money goes to a special fund that can then be tapped to assist small scale developers who want to tackle projects in inner-city neighborhoods. According to Klemm, a set aside like that could be supported if the city managed the funds properly and ensured that all developers were treated fairly. Klemm is very interested in creating a coalition with the Illinois Realtors and the Home Builders Association of Illinois to look at a variety of issues faced by developers in all areas of the city. However, older neighborhoods face the unique challenges of small lot sizes and difficulty of getting property appraisals that accurately reflect increased value, even when pockets of new construction are surrounded by as-yet unimproved older residences. “All development means taking a risk, and we need to enable everyone” Klemm said.

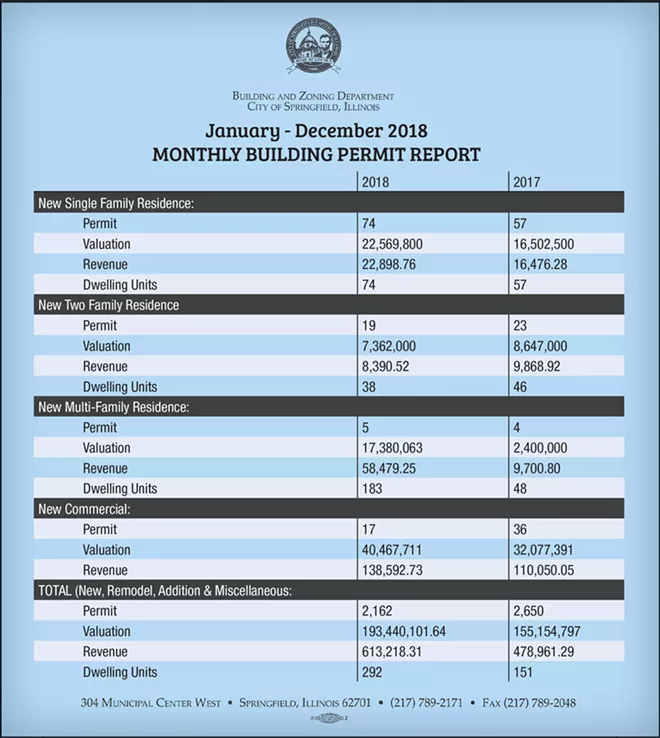

DEAN GRAVEN Another seasoned developer in the Springfield area, Dean Graven is interested in fostering ideas that could help small scale developers tackle the issues of east side redevelopment. Residential construction in the city of Springfield peaked a decade ago, with 650 new housing starts, which fell to only 74 in 2018, due to economic and demographic changes. “You can see the impact on the city in areas like CWLP, when residents from outside communities use the infrastructure but leave each night to go home to sleep,” Graven said. He would like to see the city work to get communities engaged and look at incentives for redevelopment. Often, there are local issues with oversight of processes such building permits and inspections that should go along with TIF projects. In addition, Graven has explored ways that the Federal Home Loan Bank and Illinois Housing Development Authority could work together to provide money for upgrades to single-family homes and fixed-rate loans that would make redevelopment of older neighborhoods more feasible. “It’s going to take local officials to talk to state and federal officials in D.C. to help us come up with creative ideas,” he said.

CHRIS NICKELL At the other end of the spectrum, Chris Nickell, a downtown developer, has cultivated some expertise and insights about successful redevelopment of buildings. Nickell started small, with the purchase and rehab of a building to create housing for his own family, plus another unit to generate rental income. While he has the accumulated experience of completing 40-50 residential units and another seven commercial spaces, Nickell’s primary enterprise is working for the Springfield office of American Wind Energy Management, a company that serves as a developer for wind-turbine farms throughout the country. Some of Nickel’s downtown projects have been funded in part with Tax Increment Financing (TIF) from the city itself but also through the use of the federal Historic Tax Credit (HTC), which can be used to defray the cost of rehabbing properties within designated historic districts. While this is a tool that has worked beautifully in major cities (think turn-of-the-century high rise architectural beauties on Michigan Avenue in Chicago), it’s more difficult to use on small- scale adaptive reuse projects that might bring underutilized buildings throughout Springfield back to life. According to Nickell, the HTC requires that the building owner spend at least the purchase price of the building on the renovation itself. In Springfield, where large older buildings can often be bought very inexpensively, it’s fairly easy to spend many times the purchase cost because the often-vacant buildings are in need of so much renovation. As an example, Nickell mentioned the Downtown Springfield Heritage Foundation, which is currently offering a downtown storefront of 4500 square feet for the bargain price of $30,000 to a developer who will renovate and put it back into use. According to Nickell, who has several years of experience in this very type of renovation under his belt, the clincher is trying to make the numbers work. He offered a simple calculation: If a developer were able to renovate the space, which is currently an empty shell, for $75 a square foot, the cost would be $337,500, which would yield $100,000 in tax credits. “But who can use that?” he asks. It would take a large income to use that much credit towards a tax liability. Using this financing incentive would mean bringing on a tax equity partner, which becomes a more complex undertaking than most small-scale developers, or even a developer with a few years’ experience like Nickell, can handle. While TIF funding is available to developers for the purchase and rehab of buildings located in TIF districts throughout the city, the assistance comes with an important requirement. Nickell has been successful in receiving TIF money, to use in combination with the HTC, but found that all labor for the project must then be paid at prevailing wage, which could likely increase building costs of $75 a square foot to $100 or beyond. “This prevailing wage requirement can result in a per-unit rental price above where the market rate is in Springfield currently,” he said. Other ideas that Nickell offered to help spur inner-city development include annual caps on local property tax increases in areas where redevelopment would bring buildings back to life and significantly increase their equalized assessed value, a revival of a now-defunct city program that offered $10,000 facade grants for downtown buildings, a case-by-case relaxation on requirements for such things as a window in every bedroom, (for example, when sprinklers are present), because downtown mid-block buildings often don’t have side-walls with windows and the development of a user-friendly financing model that would allow lenders to more easily work with start-up developers in the pre-application stage to calculate the viability of projects in older neighborhoods. Although Nickell comes to the table with resources, knowledge and advantages that others may not have, one of his greatest strengths is good communication and a positive outlook for the future of Springfield. “I ‘drank the downtown Kool-Aid’ long ago and continue to preach to DSI and anyone else who will listen. There is some low-hanging fruit in smaller buildings that wouldn’t be a huge lift for redevelopment,” he said. Nickell believes the overall market for downtown residential development is stable. He has a shortage of vacancies in his handful of adaptive reuse multi-unit apartment buildings and has met many younger professionals, medical students, legislators and lobbyists that don’t want a house and yard. “I’m optimistic for the rest of the city, despite the obvious downward trend in west-side development,” he said. “As a developer, I want to see more goods and services available downtown. We all need to prosper, to make it a neighborhood.”